17 Apr Wildlife Computers Lets Scientists Hitch Tell-All Rides

BY LISA STIFFLER on April 3, 2018

Originally Published in GeekWire

Researchers tag female northern fur seals on St. Paul Island, Alaska, to better understand what they’re eating and how that relates to their decline. Research conducted and photos collected under the authority of MMPA Permit No. 14327. (Alaska Fisheries Science Center’s Marine Mammal Laboratory Photos)

REDMOND, Wash. — At first, the monitoring tag revealed typical sea lion data. The mini-computer implanted in the animal detected an ordinary Steller sea lion body temperature and swimming behavior.

Then the data got weird.

The “life history transmitter” from Wildlife Computers relayed a temperature that more closely matched the chilly waters of the Gulf of Alaska — not the toasty 98 degrees of a whiskery mammal. The light-sensitive tag also indicated that it was in the dark for about a week before the buoyant monitor popped to the surface.

What triggered the dramatic plot twist?

Oregon State University scientists hypothesized that a cold-blooded sleeper shark had eaten the sea lion, then regurgitated or passed the device. When the tag floated to the surface, it relayed its data to a satellite, generating the sea lion’s “autopsy from space.”

It was an interesting result for researchers trying to save the endangered Steller sea lions; sleeper sharks are massive, slow moving creatures lurking deep in the ocean. It would have been difficult to ID these poorly understood suspects without the use of the Redmond-based company’s computerized tag.

Wildlife Computers builds tags that help researchers unlock the mysteries of fish, penguins, turtles, sharks, whales, polar bears, seabirds and seals around the world. Launched 30 years ago, the founders bootstrapped their way to a multi-million dollar company that employs 50 people. They recently moved into offices filling 23,500 square feet in Redmond.

Wildlife Computer’s CEO Melinda Holland with a heavy-weight early version of a tag in her left hand, compared to a streamline, current model. (GeekWire Photo / Lisa Stiffler)

“The push is for more information from every tagged animal,” said Melinda Holland, CEO of Wildlife Computers. “The underlying driver in the marine world is who is eating who and how much and when.”

It takes a huge skill set to get the job done. The company has electronics engineers who design the circuitry. Mechanical engineers create tags matching a species’ needs, whether that’s minimal drag in the water or buoyancy to aid in signal transmission or tag retrieval. They select materials that can withstand ocean conditions and hold up to a wild animal’s wear and tear. Software engineers design firmware and application software that can efficiently capture, transmit and serve to the researcher massive amounts of environmental data. And there are biologists who support field researchers who analyze the information.

Wildlife Computers is one of only a handful of businesses in the field.

Carey Kuhn, an ecologist with the Alaska Fisheries Science Center’s Marine Mammal Laboratory in Seattle, is a fan. Kuhn studies northern fur seals near the Bering Sea’s Pribilof Islands. The seals’ numbers have inexplicably dropped since the mid-1970s, so she’s using Wildlife Computer tags to help discover why.

“This is absolutely fundamental information about what they do once they leave the beach,” Kuhn said.

Kuhn is focused on the seals’ diet. Researchers know the seals primarily eat fish, but the tags tell them much more: how deep they’re diving, the temperature of the water and how long they’re staying under when hunting. Scientists can link that information to which fish are in the area to reveal their diet.

“All of these data help us determine what aspects of their foraging are important,” Kuhn said. Building a better understanding helps highlight which factors should be targeted in order to save the seals.

“It’s a very big question,” said Kuhn.

Electrical engineer Kris Falkowski has been at Wildlife Computers for 23 years, designing tags for a variety of marine species. (GeekWire Photo / Lisa Stiffler)

Science at the ends of the Earth

Wildlife Computers’ story also started with seals — but on the other side of the globe.

In the 1980s, Roger Hill and Suzanne Braun were researching Weddell seals in Antarctica. He was working with an advisor studying blood oxygen levels when the seals dive. She was looking at mother-pup relationships. Hill was engineering the tagging devices for his project, and was recruited to make them for Braun as well.

When the work at the South Pole’s McMurdo Station ended, other scientists asked Hill to make tags for their projects. The devices, which could weigh more than a pound, used microprocessors and transmitted data via satellite.

Wildlife Computers’ has bootstrapped its way to a multi-million dollar company with 50 employees occupying 23,500 square feet.

“It was absolutely cutting-edge technology,” Holland said.

Hill and Braun, who ultimately married, realized there might be a business in tags and moved to Seattle. They found customers with the Marine Mammal Lab at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

In 1990 they recruited Holland — whose background included computer programming, data analysis and business administration — to join them. The business got its start in the Hill’s spare bedroom and laundry room, then occupied a room over their garage and eventually moved into its own space.

Sue, who took the last name Hill, retired from the company more than 5 years ago; Roger retired 3 years ago.

In a lab at Wildlife Computers, Heather Jenkins mixes an epoxy for making tags. (GeekWire Photo / Lisa Stiffler)

The company recently moved into a new space that includes the computers and cubicles requisite at a tech company, but there’s also a chemistry lab, machine shop and an insulated chamber bigger than a refrigerator for testing the tags’ satellite signals.

There are shelves lined with boxes of circuit boards and other electronics, many of which were built for cell phones, but being repurposed for wildlife tags. Phones are a natural source for tag hardware: Both are small, data-intensive devices that run on batteries and transmit information. The mostly plastic and epoxy external cases for the tags are cast on site, and the spacious machine shop handles the construction of some metal components.

Holland remembers when Roger would carve tag prototypes out of wood blocks that were then cast in silicone to create the molds. The electronics were placed in the mold, which was filled with epoxy to create the final tag. They used Legos to build the boxes that temporarily held the silicone in place.

The engineers now use high-precision, computer numerical control or CNC machines to build the masters for the molds.

“We’ve come a long way,” Holland said.

The trick with tagging

Each tag design is its own little riddle to solve.

“Attachment is the number one challenge: How do you keep a tag on?” said Holland. The device needs to be sturdy and unobtrusive. “You want to know the behavior of an animal, not the behavior of a tagged animal.”

Some projects can use off-the-shelf designs, but others require months or years of prototyping.

Another wrinkle is data transmission. The tags collect a suite of data points, including body temperature and other biological data, swimming speed, light level, and water depth and temperature. It adds up to a massive amount of information.

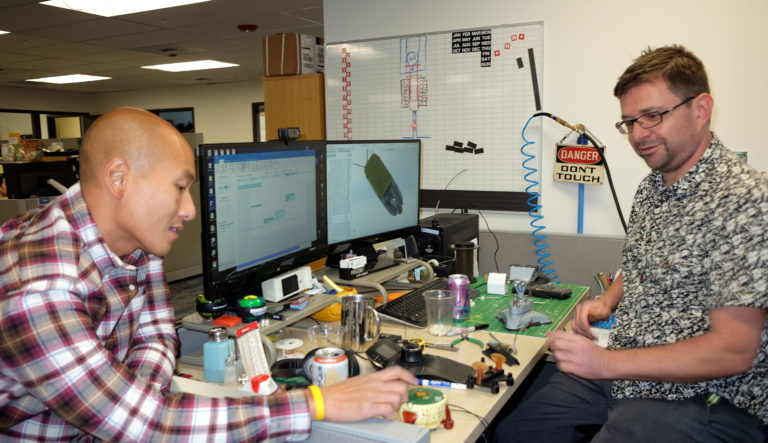

Chief engineering officer Danny Vo, on the left, and Shawn Wilton, senior mechanical design engineer, discuss a tag prototype. (GeekWire Photo / Lisa Stiffler)

Swimming animals need to come to the water’s surface long enough to send data to the Argos telemetry system, which is carried by weather satellites controlled by NOAA, the European Union and India.

For some species, you can recover a tag and download information. Kuhn, for example, gives her seals a quick haircut and recovers tags that are glued to their long fur. For other animals, the scientists recover tags that are buoyant and float to the surface after a triggered release or the animals dies.

You can start looking for patterns of the tags that would suggest that seals have consumed them. That couldn’t have been done without Wildlife Computers.

Polar bears are one of the trickier subjects. Female bears can be collared with a tag. But a male polar bear’s head is smaller than his neck so the collars slip off. Another strategy is to attach an ear tag, but when a bear shoves his head into ice holes while hunting, the tags can get knocked off.

Slow-swimming basking sharks require their own tagging strategy. The creatures don’t surface for long, so the engineers at Wildlife Computers devised a torpedo-shaped tag that is tethered to their backs. When the basking shark gets close to the surface, the tag is built to act like a kite, gliding upward to transmit its data.

Michael Schmidt is deputy director of Long Live the Kings, a nonprofit working to protect Northwest Chinook or “king” salmon and related fish. The research they support along with NOAA, local tribes and Department of Fish and Wildlife incorporates a variety of tags to track steelhead and coho salmon migration and to figure out who’s eating them and where.

For studying steelhead, the scientists insert an acoustic tag into the fish. The tag sends out a signal detected by underwater receivers located in multiple spots in Puget Sound.

Another strategy is to put a “backpack” device on harbor seals that are prevalent in the area. The backpack includes a receiver that can also detect when the fish are nearby.

Scientists place tags in the belly of juvenile steelhead. (Long Live the Kings Photo)

“You can start looking for patterns of the tags that would suggest that seals have consumed them,” Schmidt said. “That couldn’t have been done without Wildlife Computers.”

Fish tags are essential to a salmon migration game that Long Live the Kings helped create. Survive the Sound allows players to select a tagged fish that they hope will make the quickest time through Puget Sound — and avoid dying in the process. Scientists track their progress during the May migration and post results. Registration for the game started in March, and Survive the Sound lesson plans are available for free for local classrooms. The game’s goal is to increase awareness about the region’s iconic fish.

Other projects are already helping save wildlife. A study of tagged humpback whales off of the coast of Brazil led an oil company to build its offshore oil platform away from where the whales were migrating and feeding.

On the U.S. East Coast, collisions with ships is one of the leading causes of death for endangered right whales. By tracking the whales with Wildlife Computers tags, scientists were able to study their movements, ultimately leading to the adjustment of shipping lanes to avoid the creatures and prevent expensive crashes.

“Those are the kind the wins I love hearing about,” Holland said.

Learn more about Northwest marine life

The Salish Sea Ecosystem Conference is April 4-6 at the Washington State Convention Center in Seattle. The event, which is celebrating its 30th anniversary this year, features keynote speaker Sally Jewell, U.S. Secretary of the Interior under President Obama. GeekWire’s Lisa Stiffler will participate on a panel titled “Broadening the audience: Can ‘Silicon Valley North’ change the way we think about Salish Sea recovery?” Attendees include researchers, First Nations and tribal government representatives, resource managers, community and business leaders, policy makers, educators and students.